This reflection on Olivia Plender’s community room installation for Life Support was written by Julija Silyte, an undergraduate student in the School of Art History at the University of St Andrews, as part of the St Andrews Research Internship Scheme (StARIS), during which Julija conducted research for the wider research project.

Olivia Plender’s installation Our Bodies Are Not the Problem, the Problem is Power (2021): Art Facilitating Community Networks

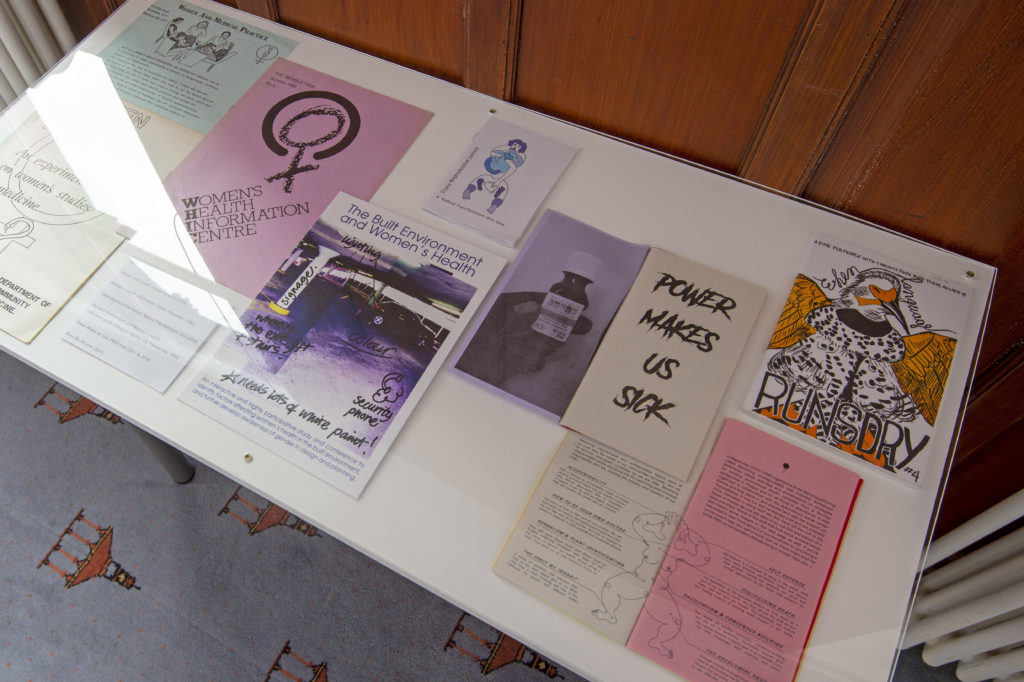

Olivia Plender was commissioned to redesign the Community Room as part of the Life Support exhibition celebrating the thirtieth anniversary of Glasgow Women’s Library. The installation was informed by research in the GWL archives, which contain zines and other publications on women and non-binary people’s health activism. The words to refurbish, to redesign, and installation are used as synonyms because the categories of fine art, design, and interior design intentionally evade art historical hierarchy here. The work Our Bodies Are Not the Problem, the Problem is Power (2021) is aimed at the community of women gathered around GWL. The Community Room is where acts of life support, care, and organising can take place. At the time of increasing commercialisation of the art world, gentrification, and underfunding of healthcare, this work (as well as the whole exhibition) points the attention back to the ways in which it is possible to maintain health and care in communal ways that emphasise solidarity.

Locally specific global struggles

Our Bodies Are Not the Problem, the Problem is Power contains curtains with a print of women involved in the women’s health compendium Our Bodies, Ourselves, first published in 1970 (Figure 1). Plender chose to focus on the transnational history of the publication rather than exclusively on its US context and the Boston Women’s Health Collective, who first published the book. As Davis highlights, although the book was compiled by a US feminist group and started from an American context, it had a broad global significance [1]. With 34 translations and adaptations, the book has been significant in various feminist circles [2]. Referring to the book, it is critical to acknowledge such a span and be aware not to impose US cultural imperialism [3].

Thus, the curtain print shows Kornelia Slavova (Bulgarian translator), Jane Pincus (co-founder of the Boston Women’s Health Collective), Liana Galstyan (Armenian translator), Marlies Bosch (Tibetan translator), Ester Shapiro (Spanish translator), Lobsang Dechen (contributor to the Tibetan edition), Toshiko Honda (contributor to the Japanese edition), Bobana Macanovic (contributor to the Serbian edition), Tatyana Kotzeva (contributor to the Bulgarian edition), Sally Whelan (co-founder of OBOS), Stanislava Otašević (contributor to the Serbian edition), Norma Swenson (co-founder of OBOS), Miho Ogino (Japanese translator), Codou Bop (Senegalese coordinator of the edition for French-speaking Africa), Toyoko Nakanishi (initiator of the Japanese edition) and Kathy Davis (author of a book on the transnational history of OBOS). Such circulation and transmission of knowledge (through the focus of Plender’s work, translations/adaptations of the book, and the exhibition about feminist forms of care) are strategies of decolonial feminism [4]. They seek to expose oppression multidimensionally treating race, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, class, age, and abilities as non-conflicting categories. Seeing feminist struggles in a global but also locally specific manner is a political move evident in this work as well.

Trans rights are key to feminist activism

Another detail of the installation is drawings of illustrations from various editions and adaptations of Our Bodies, Ourselves together with Trans Bodies, Trans Selves, whose second edition was recently published in April 2022 (Figure 2).

The drawings include women’s self-defence/martial arts class, a women’s football team, a couple with different movement abilities, a pregnancy yoga class, women doing housework, women at work, lesbian couples, and mothers, trans healthcare activists, and a figure with a serpent reminiscent of the Rod of Asclepius, referencing a visit to the gynaecologist. In other words, scenes show women and non-binary people’s healthcare, ways of sustaining life through sports, maintenance of home and family through waged and domestic labour, and LGBTQ+ people’s place within the Women’s Liberation Movement.

The latter is also referenced through the choice of the lavender colour for the walls. The colour alludes to Lavender Menace. Used as a homophobic phrase in the Women’s Liberation movement against lesbian and bisexual feminists, it was subsequently reclaimed by these same groups. After separating from National Organisation for Women, the group named themselves the Lavender Menace. The homophobic attitude in the 1970s toward lesbian and bisexual feminists echoes transphobia prevalent in some feminist groups (also known as TERF, trans-exclusionary radical feminists) nowadays. Identity is always slippery and changing; it can easily evade the cultural norms that seem to be fixed.

Anthropologically, the aforementioned exclusion is usually based on the perceived threat of seemingly stable categories of gender, sexuality, etc. In the introduction to Trans Bodies, Trans Selves, Boylan notes ‘that trans identity and trans experience are a work in progress, a domain in which the discourse itself is still in a state of evolution and growth’[5]. A deviation from a social category can surely seem threatening to the social order when looked at from the perspective of the privileged. Nevertheless, deviant agents exist in the same social order. Figuring out their identity is labour in and of itself. In a heteropatriarchal world, where narratives about gender binary are widespread, Vaccaro suggests several alternatives for thinking about gender, namely through crafts and hyperbolic geometry. Non-binary people ‘craft’ their identity by stitching the realms of law, science, biopower, and self-knowledge among others [6]. Medical administrative systems distinguish ‘before’ and ‘after’ phases of transgender life; in so doing, the systems give in to the gender-binary frame and the idea of being entrapped in an unsuitable body [7]. Hyperbolic geometry dismisses one of the main principles of Euclidian (and by extension, Western) geometry that parallel lines can never converge or diverge. Thus, hyperbolic space allows to circumvent the gender binary and understand the lived body in relation to other bodies in new forms. In other words, the supposed threat to the social order (as were lesbian and bisexual feminists or trans people) requires much labour in its formulation and space for translating it from a personal to collective labour. By reclaiming and representing these identities, Plender’s installation offers such space for sharing, figuring, and swimming through gender identities that administrative bodies seek to render legible.

Healthcare and women’s health

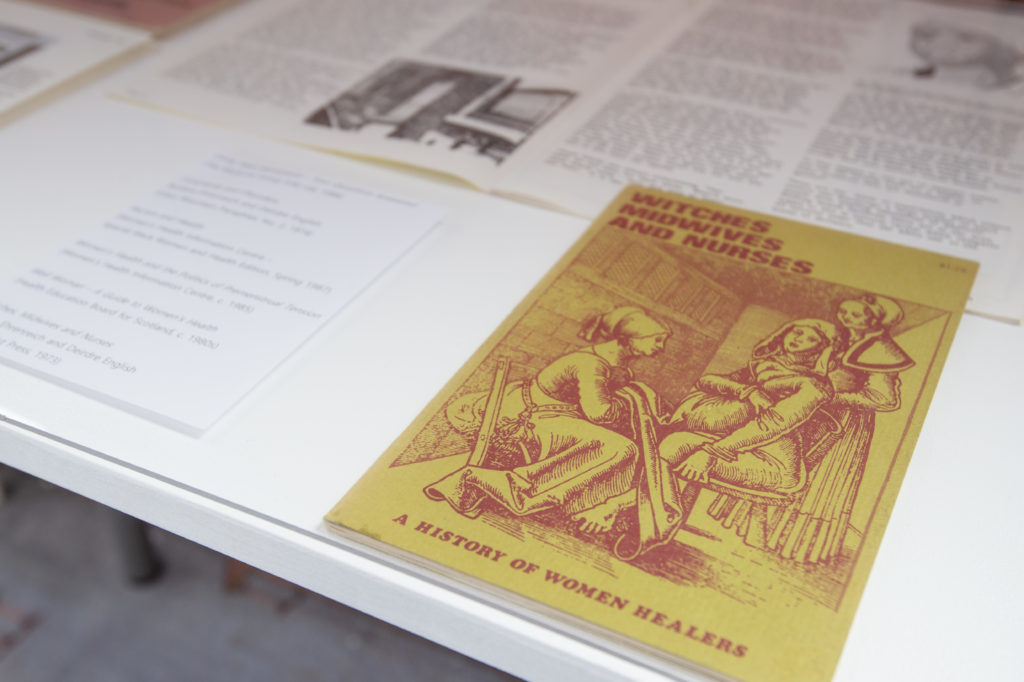

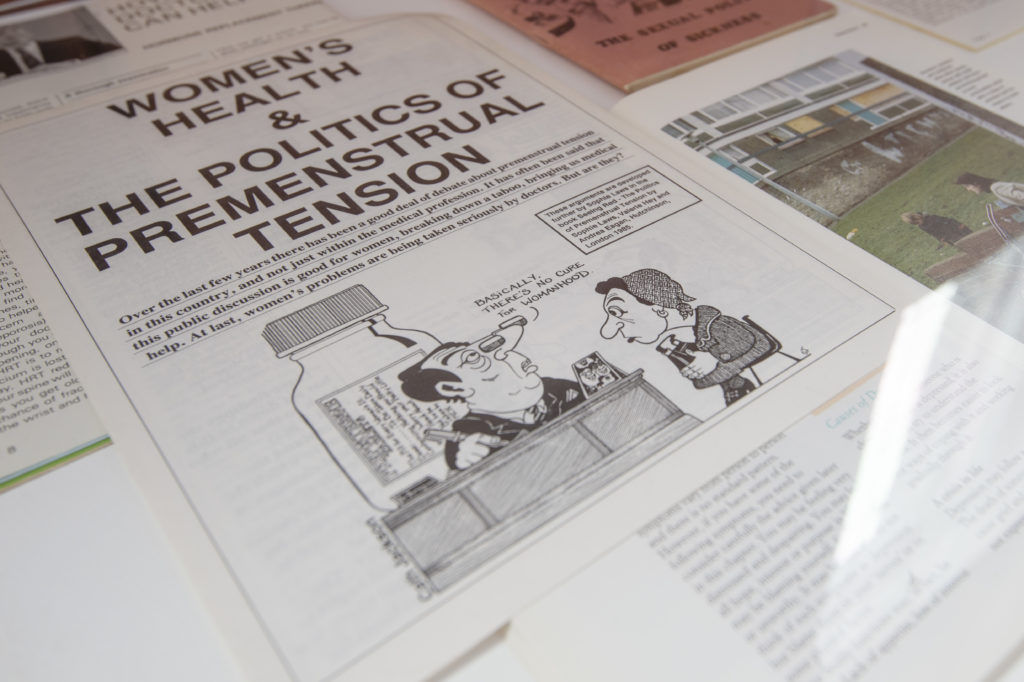

Figuring of identities often takes place in many realms – taking care of the biological body is one of them too. Women and non-binary people’s health is also a realm where one’s identity can become even more visible when faced with systemic inequalities. These questions are raised by incorporating GWL’s archival material on health activism and five different editions of Our Bodies, Ourselves, Ourselves Getting Older and Trans Bodies, Trans Selves (Figures 3-6).

Olivia Plender, in the interview with the exhibition curators, shared how:

The kind of health issues that I have barely get researched, because it’s usually women who have them. When you go to the doctor, your symptoms are often dismissed as being all in your head, so you’re left without any support [8].

This is not a singular experience. Women’s health is still an insufficiently researched field and thus instances of women’s pain are more often labelled as ‘emotional or psychosomatic’ [9]. Such under-research is largely due to the fact that the male body is usually taken as a standard in medical research [10]. Moreover, the reproductive capabilities of bodies are controlled by biopower, whose recent example could be witnessed in Poland in 2020.

However, healthcare should not only be viewed in the light of its preventive measures or the number of places in intensive care units. Healthcare is also about nourishing health through ‘adequate food and shelter, safety from toxic environments and physical violence, opportunities to develop self-esteem, and access to health education’ [11]. The act of health maintenance cannot end within hospitals or other medical buildings. Liveable conditions are human rights. The name of the installation thus can be read in this light. Our bodies are not the problem, the problem is power.

Health, institutions, and infrastructures

The problem of power and healthcare should not finish with issues of gender. Power also affects the ways in which (dis)abilities are understood. The category of what is considered ‘healthy’ in society impacts personal lives of those who question the boundaries of this category. Disabled women are especially vulnerable because of their dependence on the patriarchal systems of health care that can easily abuse them [12]. Thus, public feminist spaces are especially needed:

… coming into women’s spaces was an opportunity to be more open and to start having conversations with other people about how they manage a life with health problems, and to politicise this experience. [13]

In the Western context, health issues are usually disclosed and dealt with in isolated and isolating circumstances between the patient and the practitioner. Thus, support groups or spaces to share experiences of ill-health can uplift such alienating effects of the one-on-one relationship with a health practitioner. Such environments, as the Community Room in GWL, can provide space for discussions not only about changing identities but also about changing bodies and the infrastructures in which they exist (or are hindered from thriving). For instance, the archival material exhibited includes a programme of a feminist healthcare workshop Becoming Undiagnosable: Fostering Autonomous Health Networks and Practices. Organized in 2017 in Prague, the event was a space to explore ways of caring for one’s and community’s health outside of medical institutions. Participants learnt self-defence, emotional and physical first aid; collected plants local to Prague that can be beneficial to maintaining one’s health; had an opportunity to engage in therapeutic karaoke; heard experiences from an autonomous health clinic in Greece. This politicised perspective on healthcare prioritising solidarity acknowledged power dynamics embedded in health institutions.

Another archival material concerning power and health is The Built Environment and Women’s Health conference guide (Glasgow Healthy City Partnership, 1999) (see Figure 6). The cover of the conference guide is an image of a car park with notes identifying steps needed to be taken to make the environment more accessible. For instance, there is a need for a security phone, more lighting, and clear indications of exits and stairs/lifts, while white columns would require signage. Kafer suggests a relational/political model to analyse disabilities [14]. Rather than treating disabilities as an entirely medical issue in the sense that impairments, for instance, hinder mobility and thus ought to be ‘cured’, she suggests shifting attention to the environments in which these bodies and minds exist. From this perspective, disabilities are also a result of exclusionary ideologies and infrastructures – the conference guide makes this explicit, too. The interaction between bodies/minds and environments also shows that health is not entirely located in individual embodiments. Moreover, this interaction problematises the biological fixity of disabilities. Environments transform bodies/minds while the latter also change over time. It is critical to ‘insist on thinking about the biological body as changing and changeable, as transformable’ [15]. Thus, the political model of relationality applies not only to identities but also to embodiments. The fear of bodily loss and impairment is so prevalent in our culture that it sometimes hinders, and silences disabled people from effectively voicing their experiences [16]. Therefore, spaces, where communicating and politicising these lived experiences is possible, are crucial.

The Community Room can be inserted into the larger systems of inequalities as a community space for radical learning (Figure 7-8). One can come there to spend time without having to spend money (an increasingly rare instance with more and more public spaces becoming harnessed for and by capital.) It is a place for community and arts, which provides social services that used to be granted by the state [17]. Glasgow Women’s Library came into being as a reaction to a project of supranational cultural organisation. In 1990, Glasgow became a European capital of culture that led to the cultural regeneration of the city. Although opened in 1991, Glasgow Women’s Library grew out of an arts organisation Women in Profile, which started in 1987 to grant a place for women’s culture during the period of the cultural capital of Europe. GWL aimed at making women’s space in the city, which is historically seen as masculine, and the location of the Glasgow Boys among other things [18].

Provided the context, GWL exists as a space that supports women’s life while also providing care as recuperation from capitalist productivity, communal learning, and archiving. The redesigning of the Community Room shows art in the service of a community whose surrounding environment encourages education as an emancipating ‘field in which we all labor’ [19]. In this space, knowledge about health stems from lived experiences, is not gate-kept, builds on accumulated historical records, and becomes an act of feminist praxis.

– Julija Silyte

References

[1] Davis, The Making of Our Bodies, Ourselves, p. 5.

[2] https://www.ourbodiesourselves.org/global-projects/. Accessed 10/05/2022.

[3] Davis, The Making of Our Bodies, Ourselves, p. 11.

[4] Vergès, “Taking Sides: Decolonial Feminism,” p. 14.

[5] Boylan, “Throwing Our Voices: An Introduction,” p. 17.

[6] Vaccaro, “Wooly Ecologies of Trans Matter,” p. 281.

[7] Vaccaro, “Wooly Ecologies of Trans Matter,” p. 284-285.

[8] Plender, “Conversation with Olivia Plender,” p. 30.

[9] Criado-Perez, Invisible Women, p. 226.

[10] Criado-Perez, Invisible Women, p. 196.

[11] Sherwin, “Health Care,” p. 427.

[12] Silvers, “Disability,” p. 332.

[13] Plender, “Conversation with Olivia Plender,” p. 30.

[14] Kafer, “Introduction,” p. 6.

[15] Birke, “Biological Sciences,” p. 199.

[16] Silvers, “Disability,” p. 339.

[17] Muhammad, “The Community, the State & a specific kind of Headache.”

[18] Patrick, “Subject in Process.”

[19] hooks, Teaching to Transgress, p. 14.

Bibliography

Boylan, Jennifer Finney. “Throwing Our Voices: An Introduction.” Trans Bodies, Trans Selves. Edited by Laura Erickson-Schroth. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014, pp. 12-18.

Criado-Perez, Caroline. Invisible Women: Data Bias in a World Designed for Men. London: Chatto & Windus, 2019.

Davis, Kathy. “Introduction.” The Making of Our Bodies, Ourselves: How Feminism Travels Across Borders. Durham: Duke University Press, 2007, pp. 1-15.

hooks, bell. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York: Routledge, 1994.

Jaggar, Alison M, and Iris Marion Young, eds. A Companion to Feminist Philosophy. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, 2000. Wiley Online Library.

Kafer, Alison. “Introduction.” Feminist, Queer, Crip. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013, pp. 1-24.

Muhammad, Zarina. “The Community, the State & a specific kind of Headache,” The White Pube, February 8, 2020. https://thewhitepube.co.uk/art-thoughts/communitystateheadache/

Patrick, Adele. “Subject in Process.” Glasgow Women’s Library, 6 October 2009. https://womenslibrary.org.uk/2009/10/06/subject-in-process/

Plender, Olivia. “Conversation with Olivia Plender.” Life Support: Forms of Care in Art and Activism. Edited by Caroline Gausden, Kirsten Lloyd, Catherine Spencer, and Nat Raha. Exhibition Catalogue. Glasgow Women’s Library, Glasgow, 2022, pp. 29-31.

Vaccaro, Jeanne. “Feelings and Fractals: Woolly Ecologies of Transgender Matter.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 21, no. 2 (2015): pp. 273-293. muse.jhu.edu/article/581602

Vergès, Françoise. A Decolonial Feminism. London: Pluto Press, 2021.